An RF cavity is the equivalent of a laser optical cavity, but hosting EM waves in the microwave range rather than visible light. It is an essential component of a maser, and can be solved both analytically and numerically, so we detail how to do so below.

The motivation of using RF cavities

The reason why we need to use a RF cavity in a free-electron maser (indeed, among masers in general) is that the cavity is a resonant cavity, meaning that it causes amplification of EM waves. The precise mechanism behind why this amplification occurs is hard to rigorously explain without solving Maxwell’s equations, but the general effect is that an RF cavity is the crucial component necessary to create a maser beam.

In a resonant cavity that is typical for a laser/maser, two mirrors are placed some distance apart, and joined with a tube made of a optically- or microwave-transparent material (depending on the operating wavelength of the laser/maser). This allows EM waves to be reflected between the metal plates, but not reflect off the walls of the tube, which creates a highly-directional and focused beam.1 This page is not focused on the precise mechanics or engineering of a resonant (optical or RF) cavity; please see Guide to modelling lasers and masers for more information on the topic. Rather, it is focused on describing how to mathematically model and simulate the electromagnetic field inside and outside an RF cavity. Being able to do so will help us design better resonant cavities for high-performance masers.

A basic 2D model

Note: Our coordinate conventions are to use to denote the optical axis (direction of propagation of EM waves), and to denote the radial distance away from the optical axis, with 2D coordinate points labelled by . When working in 3D, we use cylindrical coordinates , where are still defined the same way, and denotes the azimuthal (angular) coordinate. These are chosen for consistency with our maser coordinates, as well as the typical coordinates used for describing Gaussian beams.

We consider a RF cavity of total width , aperture (hole) width , and total length , as shown in the below diagram:

Note: The above diagram is a 2D cross-section. The full 3D cavity (which has a cylindrical shape) is not shown.

To make things simpler, to start, we restrict our analysis to two dimensions only. The (scalar) Helmholtz equation for the component of the electric field is given by:

Note: The reason we can treat the electric field as a scalar problem is that we assume that there are no longitudinal modes of the electric field. That is to say, the electric field is always transverse (perpendicular) to the optical axis, or in mathematical terms, , leaving only the component left.

In our chosen coordinates and in two dimensions, the Helmholtz equation takes the form:

Using analytical and numerical means, we’ll tackle this problem in detail.

Analytical solution

Note: While the overall solution is believed to be generally correct and mathematically sound, and the quantitative result of is well-known, the intermediary steps described here may not be fully correct. Researchers are encouraged to add citations to the literature (for instance, Pozar’s Microwave Engineering) and cross-check to verify that the derivation presented is fully correct.

In two dimensions, it is possible to solve the problem analytically in a fairly straightforward fashion using separation of variables, with the following assumptions:

- The left and right walls of the RF cavity (located at and respectively) are perfect conductors, meaning they reflect all incident EM waves and neither leak nor absorb energy

- The top and bottom walls of the RF cavity (located at and respectively) are perfectly transmissive, meaning they allow EM waves to pass through freely

- The aperture is so small as to be negligible in size compared to the width of the RF cavity (that is, ), so no energy leaks out the cavity

Note: While it may appear that energy would be needlessly dissipated over the top and bottom walls of the RF cavity, this actually does not happen, since the electromagnetic field quickly becomes zero for .

With all of these idealized assumptions, together with the fact that we are ignoring the third dimension, it suffices to say that the results we will obtain will be highly approximate. However, it will prove to be useful before we tackle the much more complex problem of the 3D case, with a non-negligible aperture and non-trivial energy leakage and absorption.

Here, we will not go through the entire process of separation of variables, since it is quite lengthy and is more of an exercise in mathematics than physics or engineering. It suffices to know that after performing the separation of variables procedure, the general solution of the Helmholtz equation in our 2D Cartesian-like coordinates is given by2:

We now impose boundary conditions to find a specific solution. We want our solution to apply for all and all , and therefore must be zero, or otherwise the solution blows up at . Meanwhile, we impose the requirement that must vanish at the surface of each of the reflective boundary walls (that is, at and ); this comes from the fact that mirrors are typically made of conductive materials (typically metals), and the tangential components of the electric field at the surface of any perfect conductor is zero. Here, is the tangential component, and therefore at both ends of the cavity. To satisfy the boundary condition, must be zero. Now, if we define , we have:

Note: Here, describes the amplitude of the wave as it propagates in space, and depends on the value of . The precise value of can be found through Fourier analysis, but we will not cover this for now.

Meanwhile, to satisfy the boundary condition, we must have . Solving this equation gives us , or alternatively:

Thus, the modes that the cavity can support are directly related to the integer values of and , so they are quantized. Now solving for , we obtain:

We observe that is only real-valued if . This means that the minimum value of is given by the case where , that is:

From dimensional analysis we can tell that has the same units as , and takes the interpretation of a cutoff, prohibiting modes above a certain wavelength3. Indeed, we may define a cutoff wavelength , which is given by:

This is the longest wavelength that the RF cavity permits; it is impossible for any EM wave of a longer wavelength to be present within the cavity. Thus, the RF cavity restricts the possible modes of the electric (and magnetic) fields, allowing us to preferentially select for specific modes. Indeed, if an RF cavity is constructed very carefully to minimize attenuation/losses, then the fundamental mode dominates, and the RF cavity supports EM waves of (almost) purely one wavelength, that being . We can convert this to frequency with , and thus . For instance, a RF cavity would therefore have (in our 2D simplification) a fundamental mode with a wavelength of , and thus a frequency of around 4.

Additional information: In purely 2D space, there are only TE (transverse electric) modes in the plane of the cavity; a transverse magnetic field must point out of the plane (into the 3rd dimension) and is thus out of our consideration.

A more advanced 2D model

In our basic model of a maser RF cavity, we assumed that the aperture was negligible in relation to the rest of the cavity. This, of course, is an over-simplification. We will now consider what happens if we do consider the effects of the aperture.

The physical effect of the aperture is that it allows some portion of the electromagnetic field inside the RF cavity to pass outside the cavity. This is a complex process that is not easily modelled analytically. However, we can model it with the following boundary condition (which we may term a transmissive boundary condition):

Where is the transmission coefficient, and is a dimensionless number between zero and one that describes what percent of the energy (or more precisely, the power density) of the electromagnetic field is allowed to pass outside the RF cavity5. We will not care right now about how exactly one can derive from first principles, just that it is some known value, and is expressed as the ratio between the electric field’s amplitude at and at . That is:

Where we require that be real-valued, and thus we must take the absolute value, since can be complex-valued. This definition is useless for actually calculating what is from first principles, since it requires knowing at the left and right ends of the cavity, which (by definition) we don’t know. However, It can be experimentally-determined by performing actual measurements, or numerically-determined by performing a curve fit on the results of finite-element simulations (more on that later)6.

In addition, we can recognize some basic qualitative features of . In the limit as , then , meaning that 0% of the microwaves are transmitted (equivalently, 100% of the microwaves are reflected). This would make for excellent amplification, but would also make it impossible to extract any energy out of the interior of the cavity. Meanwhile, in the limit as , meaning that 100% of the microwaves are transmitted (equivalently, none of the microwaves are reflected). This would make the RF cavity equally useless, since all the energy is allowed to pass out of the cavity, and therefore there is no amplification that can happen. But if is somewhere in between - for instance, if is between 5-10% - it can allow for the RF cavity to still effectively amplify the EM field within, while allowing a reasonable amount of power out of the cavity. We will now solve the problem analytically to show this effect, and solve for the wavelengths (and frequencies) permitted by our waveguide.

Note: We will later see that due to azimuthal symmetry, the full 3D model produces (essentially) the same analytical solution as this 2D model. Thus, assuming azimuthal symmetry holds, the results of this calculation should be a good approximation (at least in theory) to the modes present in a real, three-dimensional RF cavity!

Analytical solution

With our new transmissive boundary condition, let us start at our general solution from before, which was given by:

Once again, we want the solution to be value for all , and therefore must be zero for the solution to not blow up as . This gives us:

This time, we don’t use the perfectly reflective boundary conditions on the left and right wall of the cavity (i.e. setting at and ). Instead, we apply our new transmissive boundary condition, giving us (after dropping out common factors):

After simplifying, we obtain:

We can remove the (direct) dependency on and by defining a new constant . Thus, after dividing all sides by , we have:

Now solving for , we have:

We may rewrite in simpler fashion by defining a new dimensionless quantity , such that:

What we see is that is negative until , after which the sign is switched and we have positive . Meanwhile, the first root of is present at . In addition, at , the value of asymptotes and therefore is ill-defined. This tells us that it is impossible for . Finally, if we still assume that the left wall of the cavity (not the right wall!) is sufficiently reflective enough to be near-perfectly-reflective, then it must be the case that at we have , meaning that (or otherwise it would be impossible for this to be the case).

All of these conditions together allow us to find the possible modes. By the requirement that , it necessarily require that , since , and thus . This reduces the problem into finding the roots of such that for these values of , we have - equivalently, to find the roots of . Now recalling that , we can rearrange to find that:

Or equivalently, we have:

Where (that is the roots of ) can be analytically solved for by solving the transcendental equation , and are given by:

Now again by the requirement that the square root be real, it must be the case that:

Therefore, the fundamental wavelength is given by:

For (that is, if 10% of the microwaves were allowed to pass out of the cavity) and , the first few roots of are numerically given by the following table:

| Mode | Root () | Fundamental wavelength | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st (fundamental) | 1.47063 | 42.7 cm | 701.7 MHz |

| 2nd | 4.81256 | 13.1 cm | 2.3 GHz |

| 3rd | 7.75381 | 8.1 cm | 3.7 GHz |

Finally, as a consistency check, let us note that occurs in the limit (where the aperture disappears and both the left and right walls of the cavity become perfectly reflective). In this case, we have:

Now setting the requirement that for both the left and right walls of the cavity (that is, at and ), as with before, this requires that . The roots of are , and thus we have:

Therefore, upon taking the requirement that the square root be real-valued, we have:

Upon which taking the fundamental () mode gives us:

This is exactly the result we obtained previously, and shows that our solution is indeed consistent as it reproduces the result of our first derivation in the perfectly reflective, zero-aperture limit.

Numerical solution

To solve the Helmholtz equation numerically, we use the finite element method with the open-source FreeFEM software. This is essential to model physically-realistic cavities that have energy losses. However, in this case, we will not consider such losses in a precise fashion, and find a numerical solution purely based off our simpler model, where we abstract away the precise physics based on a generic transmission coefficient . We interpret as combining the two sources of power losses:

- Transmission due to the aperture, which is designed to let out a portion of the microwaves

- Transmission due to power leakage from the cavity, which is undesirable but nonetheless present in any realistic RF cavity

We will also leave the 3D cylindrical case and other more complex effects for later, and consider the basic 2D Cartesian case only. While this is certainly a very crude model, this numerical simulation is intended to be for familiarization with the concepts of the finite-element method; we will eventually discuss how to perform a numerical simulation that is physically-meaningful and can yield realistic results.

A crash course in the finite element method

To speak in broad terms, the finite element method approximates a solution to a PDE as a sum of lots of simple piecewise functions called basis functions7. If we let be the -th basis function, and be a constant coefficient to multiply the basis function by, then the solution can be approximated using the sum of basis functions as:

The goal of the finite element is to find the unknown coefficients that best approximate the true solution of our PDE (the Helmholtz equation). The first step in doing so is to convert the PDE into the variational form (also known as the “weak form”) - essentially, an integral equation that contains the same information as the PDE. We’ll do this in several steps. The first step is to write the PDE in standard form, meaning that we need to move all terms to the left-hand side such that the right-hand side is equal to zero. Luckily, the Helmholtz equation is already in this form:

The next step is to multiply every term of the Helmholtz equation with a test function , and integrate the entire left-hand side. A test function is a simple function that has a well-known form, such as a polynomial. This results in:

Where denotes the domain in which we’re solving the Helmholtz equation over. Now, the crucial part of the finite element method is that we have to write this integral equation as two terms: one integrated over the domain , and one integrated over the boundary of the domain, which we denote as . To do this, we use integration by parts. Recall that the integration by parts formula in one variable says that:

The multivariable version of integration by parts takes the form:

Here, we apply integration by parts to our term . Let and . Then, we have and . So using the formula, we get:

Substituting this result back into the integral equation we got previously, we have:

We can combine the two integrals over and multiply by so that we have the simplified result in a specific order, where bilinear (that is, nonlinear) terms come first, and linear terms come after:

This is the most general variational form of the Helmholtz equation. The boundary term (the integral over ) is the one we’re most interested in, because it depends on our choice of boundary conditions (more on that in the next section). Note that in the finite element world it is common to use the following condensed notation8:

This comes from the mathematical notation for functional analysis, where the inner product of two functions is denoted or , and expands to the following integrals:

The reason we need to do all this work to get the variational form is that finite element software (like FreeFEM, which we use) can convert this to a matrix equation to solve for using the methods of numerical linear algebra. And since integrals are well-defined even over discontinuous or non-smooth domains (unlike partial derivatives), the variational form used by the finite element method means that you can solve PDEs on very complex geometries, including those with sharp corners, holes, and edges, which are commonly encountered in real-life objects; in such cases, the partial derivatives in the so-called strong form (original differential form) are ill-defined.

Setting up boundary conditions

In our simplified model, we aim to solve for the region and , where . To start, we have the transmissive boundary condition from before, where is a constant:

In practice, it is easier to set to a fixed value and then set based on the transmissive boundary condition. We can set an order-of-magnitude estimate by assuming that the interior electric field is sourced from some spatially and temporally-varying potential source , where . Therefore, we have:

Therefore, the amplitude of the electric field at is given by:

Making a basic order-of-magnitude approximation for the frequency/wavelength (which can always be refined later), we arrive at a figure for about for and a power source.

Having placed boundary conditions for the left and right walls, we now need to consider the top and bottom sides of the RF cavity. This is a more complex situation since these regions are open boundaries that allow microwaves to pass unimpeded and radiate away to ; it is in fact this particular property that allows our RF cavity to be any use at all for use in a maser.

To accurately model outgoing waves that radiate to infinity, we must use the Sommerfeld radiation condition, which, in dimensions, takes the form:

Where is the magnitude of the radial vector pointing from the origin of the coordinate system (and is always positive). For instance, the two- and three-dimensional variants of the Sommerfeld radiation condition take the form:

The requirement for this to be exact, of course, is that the domain is infinitely-large. Of course, we know that simulating infinite domains computationally is impractical. However, we can approximate this boundary condition by surrounding our RF cavity in a large circular region of radius (shown below), where (the circular region is much larger than the RF cavity). Thus, we can say that ; it may seem preposterous, but our assumption that means that the circular domain can be effectively treated as infinite.

Note: the same general idea can easily be extended into 3D: the only difference is that the circular boundary will need to be changed into a spherical boundary.

We note that since only the top and bottom sides of the RF cavity permit the unimpeded passage of outgoing waves, that is, along the axes, we must modify the 2D condition to selectively choose the axis, rather than the general distance . Thus, we have:

If the domain is very large, it is possible to approximate the radiative boundary condition with simpler periodic boundary conditions. See the visualization here for a numerical simulation using periodic boundary conditions (this simulation assumes ). Indeed, one can approximate the 2D Sommerfeld radiation condition up to first-order with9:

The solutions to this differential equation over slices of constant are sinusoids, by inspection; thus this approximation results in plane-waves propagating far away from the sides of the cavity. We will now numerically demonstrate how to compute the electric field. First, recall that our weak form was given by:

We now apply our boundary conditions on the third term, which describes an integral performed over the boundaries of the domain the problem is to be solved over. We incorporated the transmissive boundary conditions by setting and to fixed values with and . These do not affect the boundary term since by nature of being constant values (formally, by being a Dirichlet boundary condition) the gradient of the electric field is zero. However, our open boundaries at and do factor in, since they specify a non-vanishing derivative of the electric field at the aforementioned boundaries. Note that since we are considering a 2D domain , the boundary of our 2D domain is a 1D curve, so integrals over are surface integrals while integrals over are line integrals. Thus adding the appropriate integral notations, we have:

Therefore, the weak form of the Helmholtz equation for our chosen boundary conditions (and with the integrals fully written-out) is thus given by:

Where here, we simulate only the interior field (that is, the field inside the RF cavity itself); we may also simulate both the interior and exterior fields with the circular domain method described previously, but we will omit it for simplicity.

Simulation results

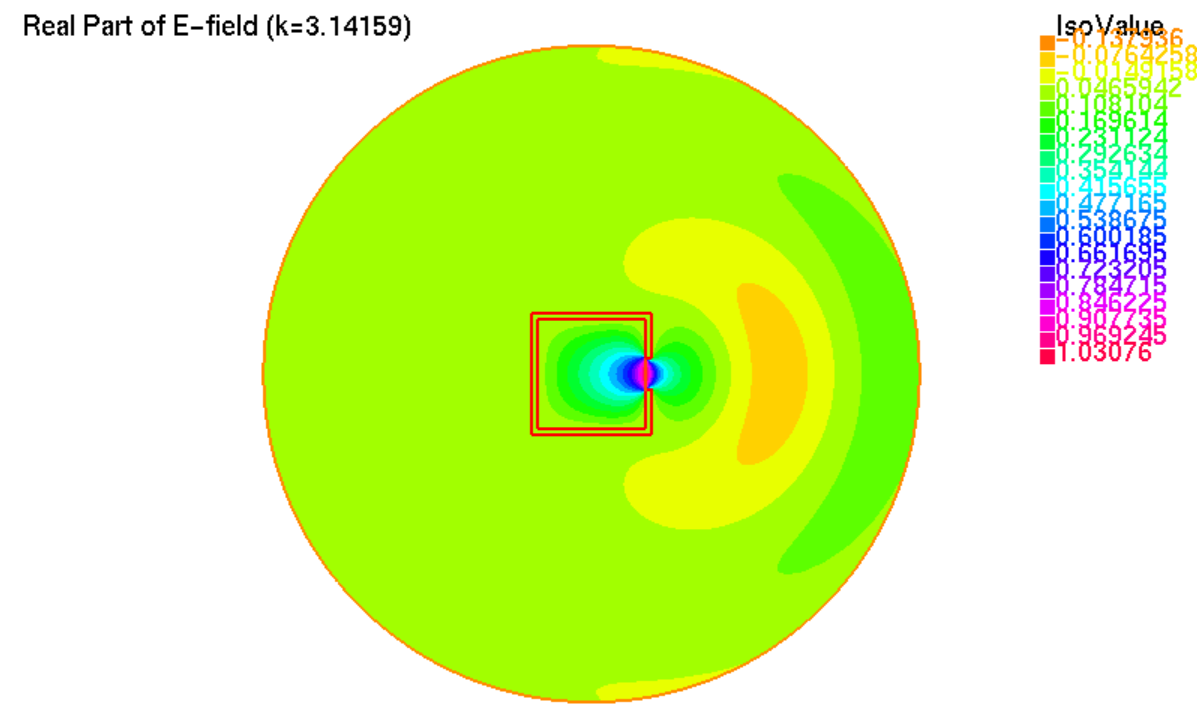

The FreeFEM code for the simulation can be found in freefem/dev/lasers/solve-Efield.edp. The result is shown below:

We see some notable features from the simulation. First, the radiation pattern rapidly decays away to infinity and doesn’t stay collimated. This suggests that it would be better to add waveguide to the aperture instead of a bare opening as the output coupler of a maser. Second, as we would expect, the field is zero almost everywhere but the interior of the RF cavity and right in front and around the aperture. Indeed, this is not very different from visible light in a dark room with a small hole in it (see camera obscura).

Note: The code does have some issues right now, including the fact that it is necessary to hard-code a value of the electric field at the aperture (here it is set to ) when in theory there should be no physical requirement for this.

The simulation also gives reference values of the electric field strengths for us to compare experimental results against, and thus improve our models. A physically-sound but impractical idea is to put a square plate in front of the maser, with lots of tiny wires crisscrossing the plate. Then, we can measure the voltage across each of the wires at regular intervals to get an approximate idea of the voltage across the entire plate (or we can interpolate numerically). Once we know the voltage we can then figure out the power density (intensity) of the EM waves and compare this against the simulation. The much more practical method is to place a sensitive antenna (or series of antennas) in front of the maser. The antenna(s) can then measure the microwave beam from the maser, much like a radio telescope, allowing us to have an accurate “picture” of how the beam spreads.

A realistic 3D model

Note: for the analytical solution, reference Pozar, _Excitations of Waveguides - Aperture Coupling (Ch. 4.8). The numerical solution will use the actual geometry with a PML. See https://pyoomph.readthedocs.io/en/latest/tutorial/spatial/helmholtz.html

Having considered a simplified 2D model, we now turn our attention to modelling a realistic cylindrical waveguide in 3D. This problem is quite complex and some aspects of it can only be solved numerically, but we will find that analytical methods can get us a long way.

Before we start, we should give some motivation for why solving this problem is necessary at all. Why, for instance, do we need to solve for a cylindrical RF cavity, and not a rectangular one? The reason is that if we want to form a microwave beam by carefully letting power out of an RF cavity, we must have azimuthal symmetry. Azimuthal symmetry means that cross-sections of the beam are always symmetric about the azimuthal angle ; otherwise, the “beam” would not be a beam, so to speak, but a propagating plane wave (with cross-sections of squares or rectangles). Thus, cylindrical RF cavities are essential for making functional masers, which is our main motivation for specifically analyzing a cylindrical RF cavity.

Second, why doesn’t a 2D approximation work? The reason is that the Helmholtz equation contains a Laplacian term (that is, ); the Laplacian takes different forms in different coordinate systems, and thus solutions to the Helmholtz equation in different coordinates are distinct. While our 2D solution might suffice as a rough approximation to a 2D cross-section of the 3D fields, it is a poor approximation in general. This means that we have to start from scratch instead of tweaking our 2D solution.

Analytical solution

We will tackle the problem in several steps - analytically to begin with, numerically afterwards:

- Solve the basic problem analytically for perfectly-reflecting walls and no power losses (that is, with no aperture and no power leakage)

- Apply a basic transmissive boundary condition, that is,

- Perturbatively incorporate the effects of lossy materials

- Find a numerical solution using finite elements

We will solve for just the TE modes, since microwave beams are approximated by Gaussian beams, which are written in terms of the electric field, not the magnetic field.

To solve, we will first expand out the vector-valued Helmholtz equation for each of the nonzero components of the electric field. Since electric fields are always transverse to the direction of wave propagation, there is no field, so we have:

Since we are solving in a problem with azimuthal symmetry, we will write out the Laplacian in cylindrical coordinates, where it reads:

We will now perform the classic separation of variables procedure. Let . We may therefore compute the derivatives as follows:

Thus if we substitute our generic form of into the Helmholtz equation in cylindrical coordinates, we obtain:

Now dividing by from all sides one obtains:

Therefore, one now obtains two differential equations, as follows:

The first differential equation is straightforward to solve; the solution is given by:

It is often more convenient to use the real-valued form:

For the second differential equation, we may solve by performing another separation of variables. First, we can multiply through by and rearrange, giving us:

We may solve this differential equation by separation of variables. Let . Then the derivatives of are thus given by:

Upon substitution, we have:

Now dividing by from both sides, we have:

Where is a separation constant. This gives us two differential equations to solve:

The first differential equation is trivial to solve; its solution is, by inspection:

Meanwhile, we identify the second differential equation as Bessel’s differential equation, whose solution are given in terms of the Bessel functions:

Where is the -th Bessel function of the first kind, and is the -th Bessel function of the second kind. Putting it all together, we thus have:

Where are all undetermined coefficients. The most general solution is obtained by summing over all possible and , giving us:

We may now apply specific boundary conditions to obtain the particular solutions for and . To begin, our requirement of azimuthal symmetry requires that we impose the periodic boundary condition . This is satisfied by default as long as is some positive integer value and if either one of is zero; if we specifically specify that then . Meanwhile, we also impose the requirement that the solution does not blow up for any value of . Because of how (the Bessel functions of the second kind) are constructed, they will lead to asymptotic behavior at , meaning that we must have to preserve a physical solution. This simplifies our particular solution to:

Note: In this particular solution, a time-dependent factor of is implied; it is not very physically important in RF analysis however, since the oscillation frequencies are in the GHz range (that is, billions of times per second) and thus we usually care only about the spatial variation of the EM field, not its temporal variation.

Note that this particular solution automatically satisfies the open boundary conditions at since the solution smoothly transitions over the sides, meaning that physically, EM waves are allowed to freely pass through. It is also physically consistent since , i.e. the solution is well-defined for all values of (and it is not hard to show that it is also well-defined for all values of and within our domain).

We must now impose specific boundary conditions that are different for and , based on the physics of the problem. First, we have the transmission boundary condition . For this to be the case, we must have:

Dividing by on all sides and defining we obtain:

Now defining , we have:

This is, in fact, nearly the exact same equation as our previous 2D result, with the only difference being that we use rather than . Therefore, the roots are also almost exactly the same, and are given by:

Solving for the values of that satisfy , we find that:

This is rather surprising in that in this case, we do not have a restriction on from the square root (as we saw before); rather, the values of are restricted based on the fixed values of .

In conclusion, we find that due to azimuthal symmetry and the radiative (open) boundaries on the lateral sides of the cylinder, our 2D treatment of the problem is actually a valid approximation*, since there is no radial nor angular dependence for the frequencies of each mode.

More on electromagnetic boundary conditions

First, a fully-reflective mirror can be modelled by a perfect conductor, which implies that the tangential component of the electric field along the surface of the mirror is zero. Second, the gain medium can be modelled by a dielectric with dielectric constant (also known as the relative permittivity). Note that we assume a linear and homogeneous gain medium; otherwise the dielectric constant is no longer constant, and is in general a tensor with 9 components (but considering the full tensorial form of would make finding an analytical solution to the problem near-impossible). Third, a partially-reflective mirror can be modelled by a dielectric with dielectric constant . By the standard electrodynamics boundary conditions, the electric fields and must satisfy:

Fourth, we know that the beam has azimuthal symmetry, and therefore we naturally have the periodic boundary condition . Fifth, the electromagnetic field in the direction (that is, the component of the field) is necessarily zero, since the laser beam points along (and thus the wave-vector must be in the form ), but the electric field is always transverse to the direction of the wave-vector (that is, ), and thus must be zero in our case. Thus we only need to solve for and (the radial and azimuthal components of the field); moreover, .

Now, upon performing separation of variables in cylindrical coordinates, we previously obtained a particular solution that could be written as a sum of Bessel functions (more precisely, the Bessel functions of the first kind)10. That is, we have found a solution in the form:

Which can be decomposed into modes as follows:

To replicate the Gaussian beam, we replace the amplitude coefficients by a continuous function (which does not depend on due to azimuthal symmetry). We may now proceed using a combination of a heuristic line of reasoning and mathematical analysis. Here, we will describe both.

In the heuristic approach, note that for the solution to become zero at and , as well as at (for the rightward mirror), it would make sense for to be the product of a Gaussian and a sinusoid (since and for a resonant cavity it is always the case that in the case of zero transmission). More precisely, we expect the Gaussian to have a radius (or more precisely, RMS width) of . Thus we assume an ansatz of the form:

Where we may write as simply since our ansatz does not depend explicitly on . Now, to obtain a Gaussian beam solution, we must replace the infinite sum in the solution with a continuous integral. The reason is because just as we have replaced the constant coefficients with a continuous function , so we must also transform a discrete sum into a continuous integral for the solution to be mathematically consistent. By substituting in our ansatz for and swapping the sum for an integral, we obtain:

The integral we see is in the form of an inverse Hankel transform. If the transform is performed, we find that the fundamental mode () for our solution is just a (simplified) Gaussian beam!

Note: Our solution is not precisely a Gaussian beam because we assumed in our calculation that the width of the beam is always constant. This cannot physically occur for since the diffraction limit tells us that all electromagnetic waves passing through an aperture must eventually diverge.

Since we are solving the exact Helmholtz equation rather than the paraxial Helmholtz equation, the solution will not be a Gaussian beam, although we can apply the paraxial approximation later on to show that the component of the field reduces to a Gaussian beam in the paraxial limit.

Note: Add the effects of impedance to describe a lossy conductor. See Ch. 1.7 in Pozar, Microwave Engineering for more information.

Numerical solution of the realistic model

Note: Finite element simulations should be added, with streamline plots and/or vector field plots of both the electric field and magnetic field, as well as the radiation pattern plot (magnitude of the Poynting vector)

To start a basic numerical model, we can start by once again assuming azimuthal symmetry implicitly, which reduces the 3D problem to a 2D problem, where we use the coordinates to denote the transverse (perpendicular to optical axis) and longitudinal (parallel to optical axis) directions, so and . The total electric field is then given by .

A typical laser cavity has a 100% reflective mirror on its left end (at ) and a partially-reflective mirror with reflectivity at its right end (it is a bit different for masers but we’ll discuss that later). The electric field satisfies the Helmholtz equation , which are essentially the time-independent Maxwell equations. When expanded into vector form, this gives us two PDEs to solve:

As mentioned, the longitudinal field runs along the optical axis (that is, ), while the transverse field runs perpendicular to it (that is, ). We assume that the left end (at ) of the laser cavity has a perfectly-reflective mirror, such that (the tangential component of the electric field is zero, which is true for all perfect conductors). This is equivalent1 to the following boundary condition:

Where in this case we have . Now, we examine the right side of the laser cavity (at ). For this side, we have a partially-transparent mirror. This means that the mirror will reflect some light and also transmit some light (we assume no absorption here).

There are several different approaches to this. The first method, and a fairly naive one10, is to start with the general form of a scattered (plane) wave:

Where is the reflection coefficient and is the reflectance, or essentially the percentage of light that is reflected. We now consider a generalized mixed boundary condition:

Substituting our solution in, we have:

Thus, we have:

This result is very interesting since it tells us that in order for a physically-meaningful reflection coefficient ( would violate conservation of energy). Now, the particular values of to make this equation true for a certain value of are actually arbitrary. For simplicity, we can set so that we can reduce one of our constants, giving us (for different and than previously):

Now, let us presume that , since again the choice of our constants is arbitrary so long as our equation is fulfilled, which also requires that . Thus we have:

The solution can be found using the quadratic formula:

Where we take the negative root since we know that . This gives us an explicit expression for in terms of . Our mixed boundary condition is then:

Finally, we obtain our boundary condition:

Where the electric field at the boundary is then given by:

For instance, for a reflective mirror and using light, substituting in and gives us . We note that in the special case of (that is, all light is reflected), we have:

This is the Dirichlet boundary condition that we would expect for a perfectly-reflective boundary in one dimension. Meanwhile, in the case of (that is, all light is transmitted), we have:

Which describes outgoing plane waves , as we would expect. This is a very crude method and a realistic simulation would most likely use a partially-absorbent boundary condition to model the fact that the mirror at absorbs some light.

Note: in addition to what has been mentioned, realistic laser cavities typically use parabolic/spherical mirrors instead of flat mirrors, so the domain will be curved at either end, making things much more complicated.

Meanwhile, the sides of the laser cavity are usually glass or some other optically-transparent material, making it an open boundary (also called a radiative boundary). This can be modelled by a perfectly-matched layer that allows light to freely pass through. While counterintuitive, this is what maintains the strong directionality of the light along the transmission axis () and keeps it as a beam rather than dispersing.

However, a PML requires a bit of work to implement, so it is often easier to just use the first-order approximation of the Sommerfeld radiative boundary condition:

Putting everything together, we arrive at the following boundary conditions for the electric field inside a laser cavity (although it can be generalized to the outside field as well):

- The aperture has a Sommerfeld-like radiative boundary condition

- The two “mirrors” of the RF cavity (really, they’re just metal plates and don’t have to be polished) have a reflective (homogeneous Dirichlet) boundary condition

- The rest of the RF cavity (including the “tube” connecting the two mirrors) also has a Sommerfeld-like radiative boundary condition; this represents a material transparent to microwaves

In this case, it is easier to use cylindrical coordinates , where is the optical axis (direction of propagation) and are the radial and polar angles respectively. We again assume our cavity to have length . Our boundary conditions for the Helmholtz equation thus correspond mathematically to:

Where our domain is given by , and we want to pick a suitably large simulation domain (where and , roughly) to be able to see both the near-field and the far-field behavior of the beam. Our first two boundary conditions encode the fact that the electromagnetic waves in the cavity must reflect off the two mirrors at each end of the cavity. Meanwhile, our last two boundary conditions encode the fact that the electromagnetic waves must pass freely through the tube connecting the two mirrors, as well as the aperture (output coupler) at the end of the cavity. Our last boundary condition enforces azimuthal symmetry since we expect our solution to be symmetric with respect to . While it may appear that energy would be needlessly dissipated over the sides of the maser, this actually does not happen, since the electromagnetic field quickly becomes zero for .

Note: This means that the resultant electric field will be complex-valued; we take only the real part for a physically-meaningful solution.

Maser gain analysis

Lastly, we don’t just want to see what the beam’s wave profile; we also want to know how well the maser amplifies light11. The corresponding quantity of interest to us in the numerical simulation, which describes this amplification, is called the gain of the maser. The gain compares the output power of the maser to that of an isotropic (point-source) radiator. It is usually measured in decibels (dB), which are a logarithmic unit, and it can be written as:

Where (in cylindrical coordinates we have ), is the input power used to drive the maser, the power of the maser is given by , and is just the Poynting vector. The input power , where and are the driving current and voltage used to power the maser respectively. If we substitute our analytical solution, we find that:

Where here, is the maximum intensity of the beam. Thus the gain is approximately:

If we assume that the initial intensity is equal to the input power (that is, we assume that the maser is 100% efficient mechanically-wise), this gives us:

Note that our result is independent of angle and also independent of . However, this is not entirely accurate, as again we are using a simplified solution as opposed to the physically-accurate solution (the Gaussian beam, where ). For a Gaussian beam, the gain becomes:

Where we used the fact that for . This result can be simplified and written explicitly, up to some constants, to:

It is easy to see that in the limit as , we have . Thus, at its source, a (perfect) Gaussian beam would have effectively infinite gain, which corresponds to infinite amplification of light (once again, here “amplification” means “concentration of energy” not “increasing energy”). Of course, as increases, the gain of the beam decreases; at some finite distance, (meaning that the Gaussian beam has diverged to the point that it is effectively isotropic and no longer performs useful amplification of light). A minimally-divergent Gaussian beam (whose profile does not change much as increases) would thus have very high gain; a highly-divergent Gaussian beam would have very low gain. Therefore, decreasing the divergence of a Gaussian beam is absolutely fundamental to improving its amplification and thus its efficiency.

Footnotes

-

This is due to the transverse and longitudinal reflections interfering with each other, leading to the buildup of undesired non-Gaussian modes in the RF cavity. In simplified terms, any off-optical-axis reflections will interfere with the desirable on-axis reflections, causing power to be dispersed and the beam to lose directionality. ↩ ↩2

-

From Wolfram Mathworld’s article article on solving the Helmholtz equation in cartesian coordinates. Owing to our coordinate conventions, we make the substitutions . ↩

-

This follows the derivation in Pozar, Microwave Engineering (4th ed.) in Chapter 3.2. ↩

-

For more information, see the Wikipedia article on RF waveguides ↩

-

This was inspired by the boundary conditions described in Freund & Antonssen’s Principles of Free Electron Lasers (4th ed.), ch. 9.1-9.4 as well as the discussion on the transmission coefficient in hole-coupled free-electron lasers from Varro et. al., Free Electron Lasers ,Ch. 3, pg. 68 ↩

-

Directly based off Varro et. al., Free Electron Lasers ,Ch. 3, pg. 68 ↩

-

This is only a basic overview of the finite element method - more details and a much more comprehensive guide to the finite element method can be found on the COMSOL software blog. ↩

-

This comes from the form shown in the documentation for the

pyoomphlibrary. Note that we swap the order of the inner products, but this does not affect the results since the inner product is commutative. ↩ -

Taken from an oomph library example for solving the Helmholtz equation with the finite element method. ↩

-

This is a simplified form of the solution given on Wolfram Mathworld’s article on solving the Helmholtz equation in cylindrical coordinates. In particular, we choose so that the solution does not blow up (become infinite) at and at . ↩ ↩2

-

Technically-speaking, a maser (or laser) doesn’t amplify light; at least, not in the sense of producing more (radiant) energy than the energy used to power it. Rather, “amplification” is a rough term that describes the fact that a maser concentrates light so that it is amplified in one particular direction, while reduced in all other directions. ↩